I first met Jesus at the age of fifteen. As a teenager, I “accepted Christ” and began to live as best a Christian life as I could muster. And it was great. I was happy as an Evangelical Protestant. I hadn’t rejected Catholicism, I didn’t know much about it and what I knew, sadly, had come from rather poor sources. From Catholics who, themselves, didn’t know much about their faith either.

Bad Catholics.

But when an Evangelical Pastor, and good friend, asked me, “What’s more important, the Bible or Tradition?” He stumped me.

[See also: How to Avoid Converting to Catholicism, in 8 Easy Steps]

[See also: What Changed This Protestant’s Mind About the Eucharist]

My journey to begin to answer that question led me to begin reading about Catholicism. I’d made a fatal mistake and would learn later that I had begun to, “be fair,” to the Catholic Church. A mistake which famous convert G.K. Chesterton calls the first step towards conversion.

If “being fair” to the Church was the first step I took then reading the Early Church Fathers, for me, must’ve ranked somewhere amongst the final ones.

It was after reading from these, the earliest Christian sources after the New Testament, that I found myself finally roundly convinced of the enduring truth of Catholic Church. It was the Church Fathers and, namely, one all-encompassing quotation, that convinced me to be a Catholic.

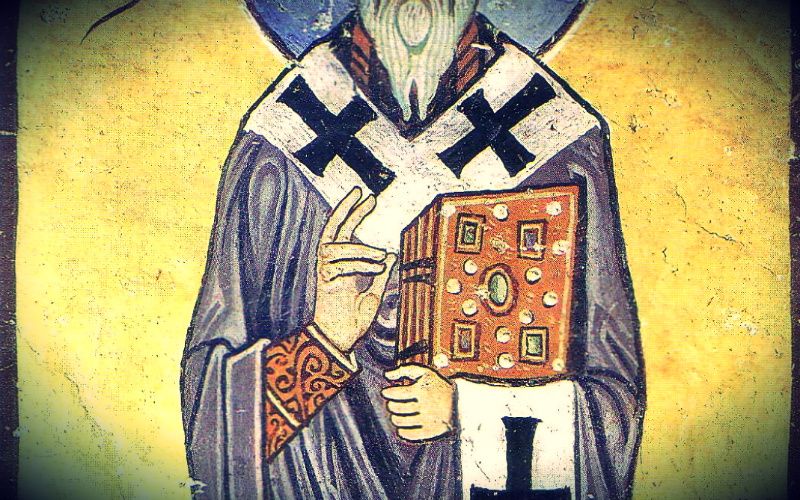

St. Ignatius, Bishop of Antioch

St. Ignatius of Antioch lived and wrote from about 35 to 107AD. Ignatius was, by all accounts, a disciple of St. John the apostle. That St. John. The author of many important bits of the New Testament, including one of the Gospel accounts and the Book of Revelation. The St. John to whom Jesus entrusts Mary, his mother. The same St. John.

Ignatius was his student and learned what he knew about Christ and what He taught from someone who had sat, and learned, at His very feet.

The writings we have from St. Ignatius of Antioch aren’t exhaustive but they are, as I found out, of incredible depth.

Written largely while in prison, Ignatius writes to a number of Christian communities, in his capacity as a duly appointed bishop of the Church. Much like the New Testament epitles by his teacher, St. John, or those of St. Peter or St. Paul, Ignatius instructs, corrects, and encourages with apostolic authority.

On the whole it’s difficult, I’ve found, to read the Early Church Fathers without seeing the reality of the Catholic Church. But in St. Ignatius, in his Epistle to the Philadelphians, I found such a singular, convincing quotation, that it was nothing I could do but assent to the truth, authority, and beauty of the Catholic Church.

This is the one quotation that convinced me to become a Catholic.

Ignatius writes,

Make no mistake, my brothers, if anyone joins a schismatic he will not inherit God’s Kingdom. If anyone walks in the way of heresy, he is out of sympathy with the Passion. Be careful, then, to observe a single Eucharist. For there is one flesh of our Lord, Jesus Christ, and one cup of his blood that makes us one, and one altar, just as there is one bishop along with the presbytery and the deacons, my fellow slaves. In that way whatever you do is in line with God’s will.

Do you see why Ignatius was so utterly convincing?

Schisms and Heresy

Like St. Paul before him, St. Ignatius, in his capacity as Bishop of Antioch, is writing with authority against those who break off from the Church founded by Christ.

Anyone, says Ignatius, who walks in heresy—that is, against the teachings of Ignatius and the other appointed Bishops—is, alarmingly, “out of sympathy with the Passion.”

An incredibly stark picture indeed and an incredible demonstration of authority which made one thing very clear to me: Bishops in the Early Church had an authority derived from Christ.

What’s more, breaking from communion with that authoritative structure—striking out on one’s own and dissenting from the Church’s teachings—was expressly condemned in the strongest sense by Ignatius.

Christians would work break off from the Early Church were seen to be “out of sympathy” with Christ and the authoritative structure He put in place.

It was clear.

The Eucharist is the Blood and Body of Christ

Next, St. Ignatius speaks unequivocally about the Eucharist as “one flesh of our Lord” and “one cup of His blood.”

This cannot be misunderstood.

Like many of the other Early Apostolic Fathers—and on this they are unanimous—Ignatius writes about what Catholics refer to, theologically, as the “real presence.”

That is, Jesus is actually and miraculously present in the Communion elements and in contrast to what I’d believed about the symbolic nature of Communion as an Evangelical.

Jesus is actually there; the act is not merely symbolic.

In other words, here is another Catholic teaching, one which we can see, clear as day, from the very beginning of Christendom.

One Bishop

I’ve written before how my picture of the Early Church was based on something of a fantastical reading of Acts of the Apostles.

I thought, and was taught, that the Early Church was a loosely based collection of “house churches” where Christians got together to study the Bible and fellowship together.

While is this partly true as I read the Early Church Fathers, these earliest Christians after the apostles, I found something starkly different in many ways.

The Early Church had an authoritative structure and here, in Ignatius’s letter to the Philadelphians, is another plain-as-day example.

Ignatius writes that we must be united, as Christians, under an authority structure which comes, ultimately, through Christ.

The picture he paints is profound: Just as there is one Eucharist—that is the flesh and blood of Christ—and just as there is only that one sacrifice, there is also only one bishop, and under him his appointed teachers and helpers. We must be united, under this bishop, as under Christ. Or, through Christ in union with the bishop.

Incredible.

Not Convinced? Keeping Reading!

St. Ignatius of Antioch was fundamentally convincing for me.

Here was a disciple of St. John speaking against setting out on one’s own, outside of the authority of the Church Christ founded. He speaks, likewise, about the importance of submitting to bishops and their appointed authority and how, remarkably, all of this centers back around the beauty of the Eucharist and Christ’s once-for-all sacrifice.

Where Jesus is really present in Communion.

But if you aren’t convinced, as they used to say on Reading Rainbow, don’t take my word for it.

Read.

A simple Google search for ‘Early Church Fathers’ will bring up about a dozens places to read them online. Or pick up a paperback translation. I purchased the whole Apostolic Father’s collection for $2 as an eBook.

Read.

As an Evangelical, I was wholly ignorant of the Church Fathers, even as a History Major in University. My understanding of the Early Church was based on a very narrow reading of the Acts of the Apostles and select tidbits from the Epistles. I was ignorant of the concept of the successive, authoritative structure of the Church found roundly in Ignatius’s writings as well as the clear language and belief about the Eucharist.

I missed it because I didn’t read.

When I read, when I explored what Church Fathers like Ignatius were actually writing about, I was convinced. I was convinced that Jesus established a Church, authoritative in nature, which will continue until the end of time. I was convinced, also, of the Catholic teaching of the real presence because there it is, as early as Ignatius of Antioch, and there it continues to be for the subsequent two thousand years.

I was convinced and although I did explore alternatives in the Anglican and Orthodox churches I found most resoundingly the teachings of the Early Church Fathers reflected, beautifully, like a mirror, in the Catholic Church.

Originally posted on The Cordial Catholic

[See also: 23 Food Apparitions Sure to Convert Any Skeptic]

[See also: 1,782 Years Old: Inside the Oldest Church in the World]