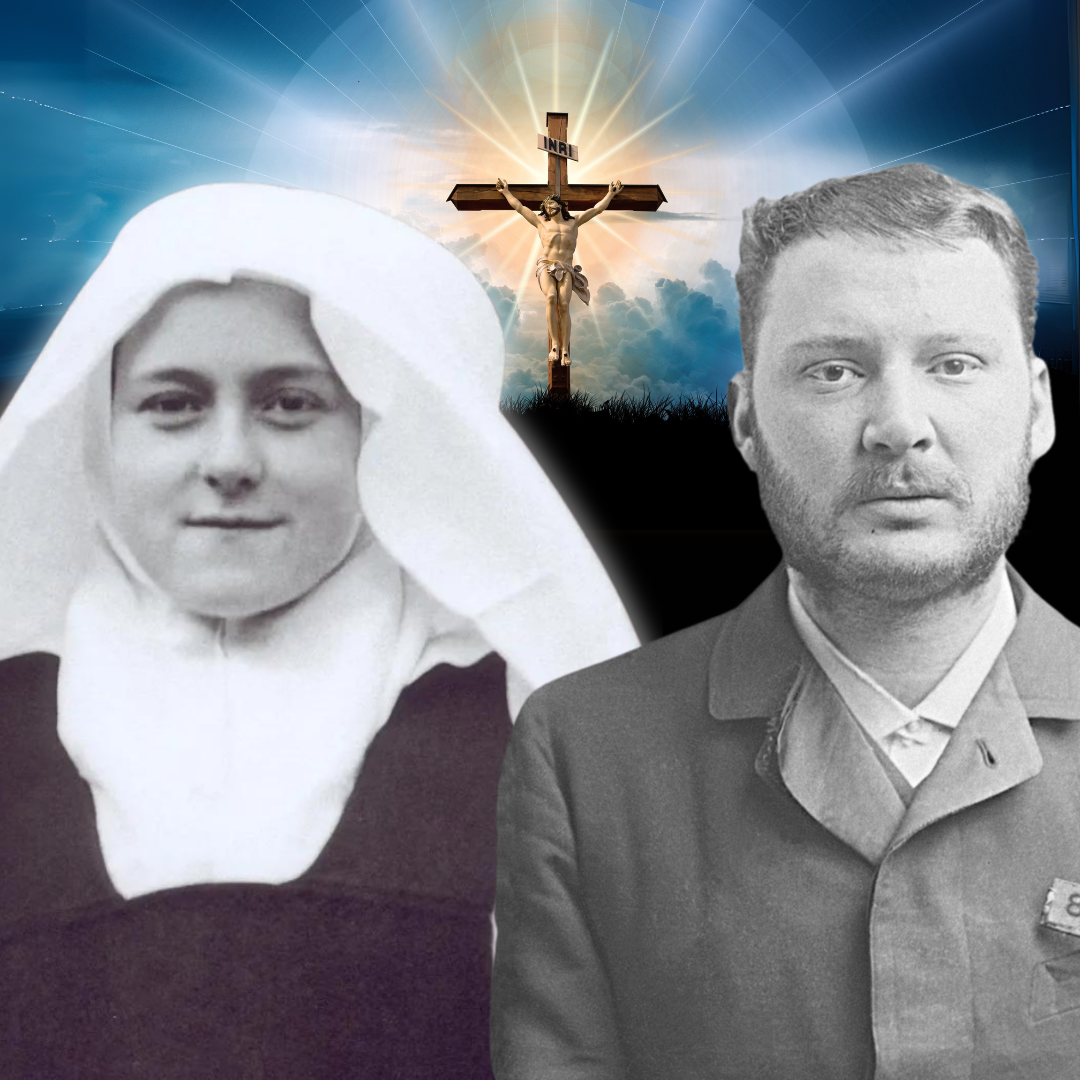

Around 1887, in Paris, a man named Henri Pranzini brutally murdered his lover, her 12-year-old daughter, and their housekeeper. The case shocked all of Europe.

Pranzini was sentenced to death, but he refused every attempt by priests to visit him, declaring he wanted nothing to do with God.

In Lisieux, however, a young Thérèse heard of the case. God stirred her heart with mercy for this man, and she began to pray intensely for his conversion. For two months, she offered prayers and sacrifices, but news reports insisted he remained hardened and refused all priestly counsel.

Then, on the day of his execution, something extraordinary happened. Before the guillotine fell, Pranzini suddenly asked the priest present for a crucifix and kissed it three times.

For Thérèse, this was the sign she had begged for: her “first son” had turned back to God at the very last moment.

Her example reminds us: no sinner is beyond the reach of God’s mercy.

What the Church Teaches About Crime and Punishment

The Catechism of the Catholic Church teaches:

The State's effort to contain the spread of behaviors injurious to human rights and the fundamental rules of civil coexistence corresponds to the requirement of watching over the common good. Legitimate public authority has the right and duty to inflict penalties commensurate with the gravity of the crime. The primary scope of the penalty is to redress the disorder caused by the offense. When his punishment is voluntarily accepted by the offender, it takes on the value of expiation. Moreover, punishment, in addition to preserving public order and the safety of persons, has a medicinal scope: as far as possible, it should contribute to the correction of the offender. (CCC 2266)

In other words, it is the State's role to punish those who commit crimes, and the Church recommends that the punishment be proportionate to the offense.

The Question of Legitimate Defense

But what about confrontations with criminals that end in death?

The Catechism addresses this in paragraph 2265:

"Legitimate defense can be not only a right but a grave duty for someone responsible for another's life. Preserving the common good requires rendering the unjust aggressor unable to inflict harm. To this end, those holding legitimate authority have the right to repel by armed force aggressors against the civil community entrusted to their charge." (CCC 2265)

Does this mean that “a good bandit is a dead bandit”?

No. A good criminal is not a dead criminal. A good criminal is one who serves his sentence and, through God’s mercy, has the opportunity to repent and be transformed. This can be made possible through concrete acts of mercy, such as prison ministry visits and—most importantly—through our prayers. After all, visiting prisoners is one of the works of mercy instituted by our Lord (cf. Matthew 25:31-46).

The Call for Us Today

The poet once said, “Crime takes over the city and society blames the authorities.” And yet, when the authorities act, there are always movements that claim to defend human rights but, in reality, only shield criminals from justice.

The Church gives us a clear response: justice must be served, but always in proportion to the crime, always with mercy in view, and always with hope for the sinner’s conversion.

Just as Saint Thérèse prayed for Henri Pranzini’s soul, so too are we called to pray for sinners—even those society deems irredeemable.

Let us never stop interceding for conversions.